About the Project

The idea behind this blog is to publish full transcripts of Edward Lear’s diaries ― from 1 January 1858 to 12 May 1862 ― 150 years after they were written. In order to make up for the delay in starting, 1858 will be posted in instalments of about five entries per day, so as to be able to start 1859 on 1 January 2009 and then proceed one entry a day until 12 May 2012, the bicentenary of Lear’s birth.

Edward Lear’s journals consist of thirty volumes covering the second part of his life, from 1858 ― when he was 46 ― to 1887 ― the year before he died. They are housed in the Modern Books and Manuscrips department of Houghton Library, Harvard College Library, Harvard University (MS Eng. 797.3).

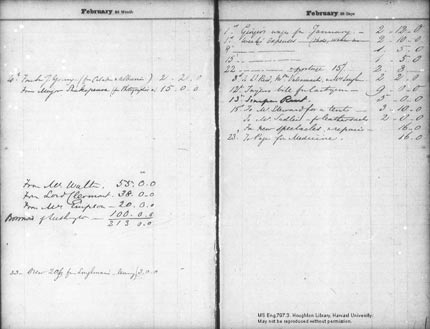

Lear used Letts’s Diaries, format no. 8, in the version with cash columns ― though he seldom, if ever, used these. Income and expenses are recorded in additional pages at the end of each volume:

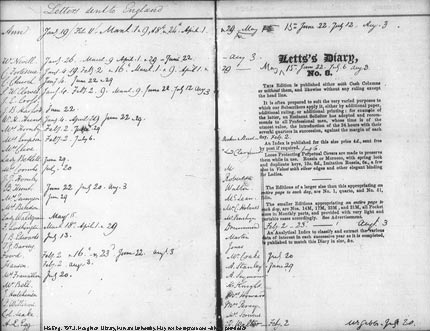

He also often used blank or advertising pages for the Diary to create indexes ― 1858, for instance, opens with a list of “Letters sent to England,” which Lear probably compiled at the end of the year:

Nothing remains of the earlier years, Lear himself appears to have destroyed the volumes covering his Knowsley years:

a curious discovery I have made lately in looking over old things of my dear sister Ann’s. I remember telling C F. that for 12 or 13 years when at Knowsley, I kept a journal about everything and everybody, but one day in 1840, I burnt the whole. It has all turned up again, for I copied out all, or nearly all, in letters to my sister, and she preserved all those, and here they are! (LEL, xix)

In a letter to Chichester Fortescue of 30 April 1885 he mentioned he still had “60 volumes of Diaries” (SL, 269) so the missing volumes ― which presumably covered Lear’s early years, apprenticeship as a lithographic artist, his work as a zoological draughtsman and, of course, the origins of his nonsense writings ― probably still existing at Lear’s death, must have been destroyed by his executor, Franklin Lushington, either because he considered them too personal or of no importance.

The choice of Lushington as an executor was unfortunate as he seems to have had little consideration for Lear as an artist or poet, although he certainly appreciated the person. After his death Lushington wrote to Mrs. Charles Street (12 May 1888; Noakes 1985, 199):

He has always been the most charming & delightful of friends to me; & apart from all his various qualities of genius, I have never known a man who deserved more love for his goodness of heart & his determination to do right; & I don’t think any human being knew him better than I did. There never was a more generous or more unselfish soul.

All Lear’s “qualities of genius,” however, had not deterred Lushington from advising Emily Tennyson against purchasing Lear’s watercolours:

He has been making some very beautiful & careful watercolour drawings of various views in Corfu for 12£ a piece… Nevertheless I should say, don’t waste your monies on them. (Lushington to Emily Tennyson, 20 June 1856; Noakes 1985, 193.)